Hala Mirowska:

In the marketplace next to Hala Mirowska, vendors sell plums, raspberries, massive bunches of dill, mushrooms fresh from the forests, dried fish and pastries. It’s so crowded that it takes an hour to cross from one end to the other. Despite this, it’s quiet. Everyone speaks softly and lines up with the most utmost courtesy. (After you. No after you, I have lots of time…). The sun is pale and gently warm. Plums which are moldy or otherwise unacceptable roll about on the ground and are stepped on, releasing a wonderful smell.

Out of this shifting, whispering mass of people, someone approaches me. He is about seventy, tall and elegant, with a long nose and a heavy leather coat. He stops before me, bows deeply, says ‘Welcome to Warsaw’, and continues on his way. It feels as though the city itself has sent me its greetings.

Muranów:

Muranów was once home to the Jewish Ghetto. If it weren’t for a small plaque next to a small piece of the ghetto wall, I’d have never known. In the center is the synagogue which is locked for Rosh Hoshanah. Next door, there’s a kosher grocery store, and I go inside. The owner is asleep behind the counter but wakes up when the door jingles and greets me in Hebrew, Polish, and English. As I browse, he nods off again. His eyes are tiny and distant behind a pair of the thickest glasses I’ve ever seen.

Since I’m already in Muranów, I visit Krochmalna Street, a street I feel intimately acquainted with through the stories of Isaac Bashevis-Singer. It’s almost entirely empty and boarded up. Gone are the the cobblestones, the balconies hung with wash, the yeshiva, the ritual baths. Gone is the smell of burned oil, rotten fruit and chimney smoke. There’s nobody around. There’s an electronics store, a salon, and a pawn shop but all the shopkeepers have gone home for the day. At the end of the street is Bashevis-Singer park, where two teenagers are making out next to an overflowing garbage bin.

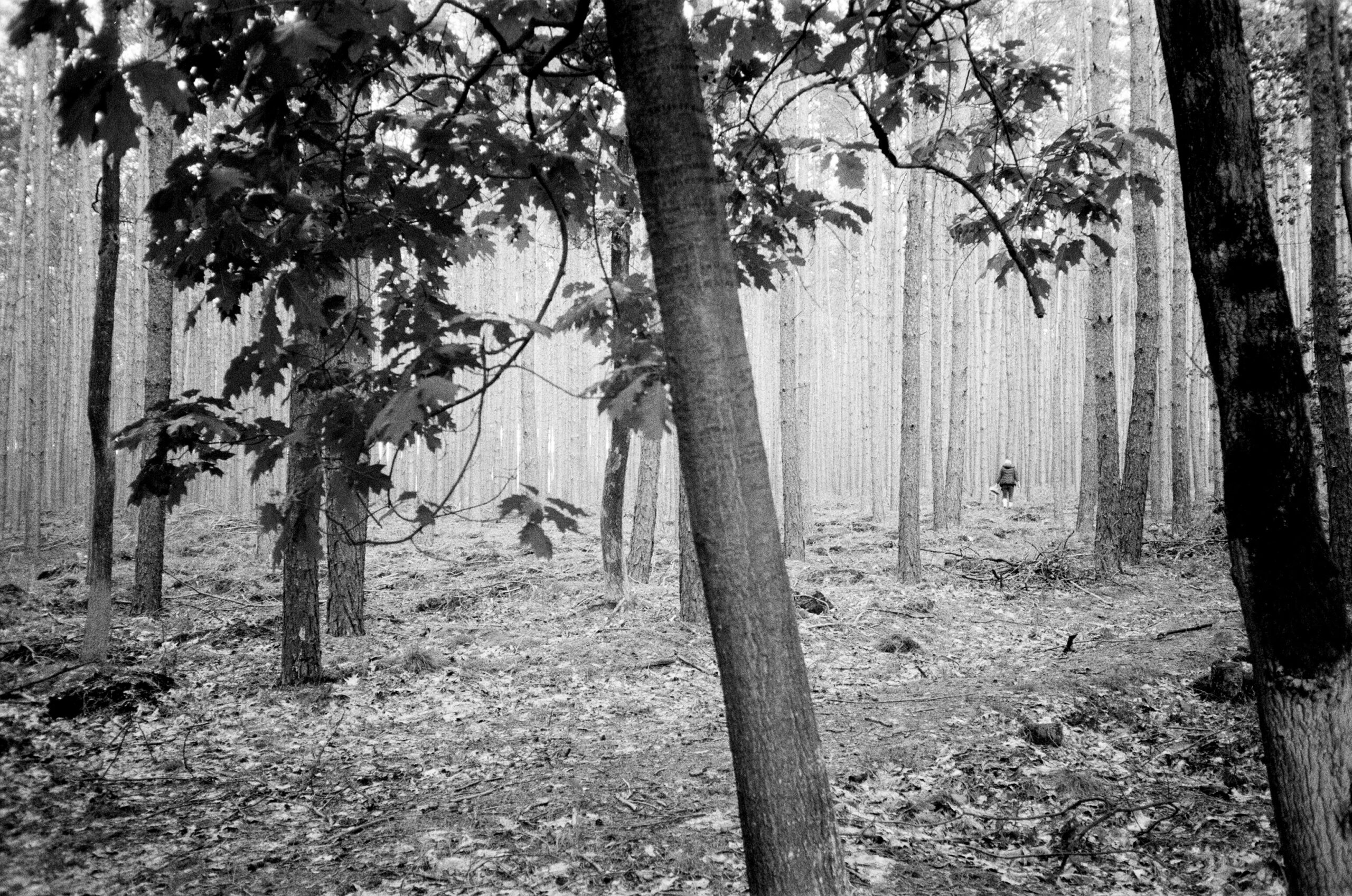

Przy Bażantarni Park

On Sunday Warsaw celebrates the Patron Saint of Warsaw, Saint Wladyslaw from Gielniowo. In the Przy Bażantarni Park in an outer district of the city there is a kind of carnival. The air there is filled with the smell of sausages, candy, fried potatoes and brass music. There is a makeshift dance floor, and it is full. The old know all the words to the songs and mouth along as they dance. The young know neither the words nor the steps. A young trumpet player from one of the bands teaches me the mazurka.

As with many parts of Warsaw, Natolin is full of hurriedly and notoriously badly built grey apartment blocks (Bloki, as they are called in Polish) that loom around and press in on the park, but as with the other districts, they seem to shrink next to the people of Warsaw, who are warm, stylish, and unpretentious.

‘Although I don’t speak Polish,’ writes John Berger, ‘the European country I perhaps feel most at home in is Poland. I share with the people something like their order of priorities. Most of them are not intrigued by Power because they have lived through every conceivable kind of power-shit. They are experts at finding a way round obstacles. They continually invent ploys for getting by. They respect secrets. They have long memories. They make sorrel soup from wild sorrel. They want to be cheerful.’