Fifth stop: Vienna! The capital of Austria is a city of culture and history. By the Danube, the city’s first traces of human settlement trace back to 500 BC. From the 15th century onwards, it was also the house of the Habsburgs, a royal dynasty that ruled for hundreds of years and played a pivotal role in the history of Europe. Its marvelous Baroque beauty hides hints of the impact WWII had on the city and on the country.

[A view of the historical city center of Vienna]

* DURING WWII *

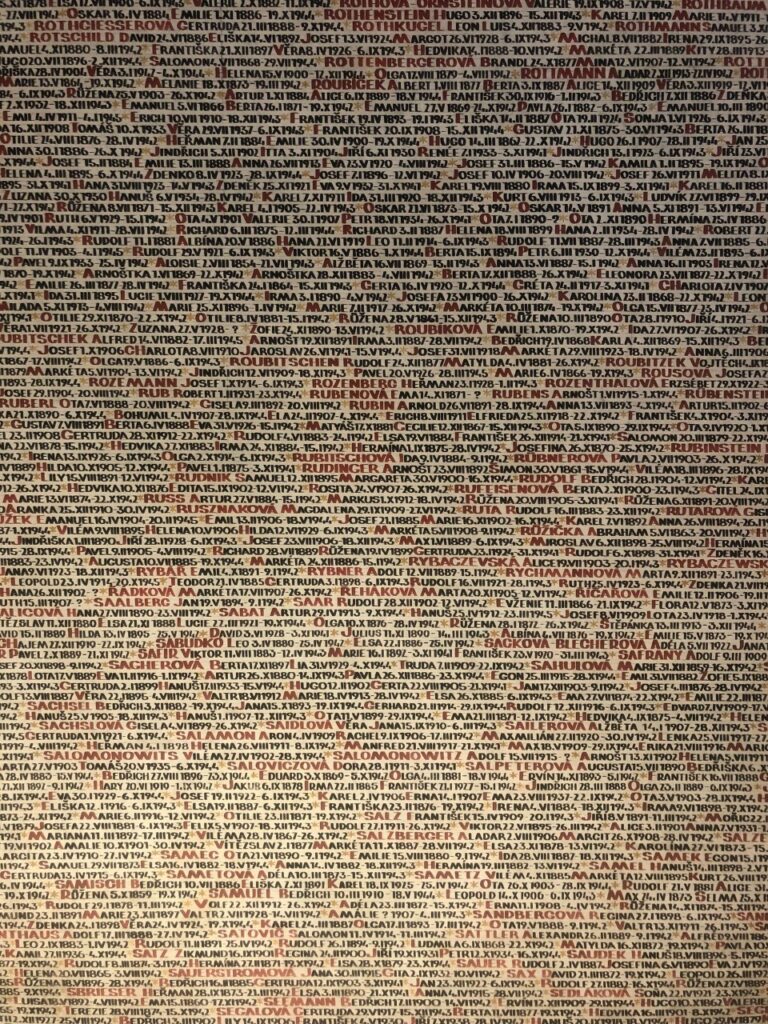

Vienna was annexed by the Nazis in 1938, right before the beginning of WWII, in an ostentatious parade that counted with the presence of Hitler, who was himself austrian born. The occupation – known in German by Anschluss – lasted until the end of the war and brought tremendous suffering and loss. Local jews were persecuted and deported and the city was besieged and bombed a couple of times both by the Americans and the British, specially by the end of the conflict.

After the end of the war in Europe, similarly to Berlin, Vienna was divided and governed by the winning allied forces – which is depicted in the famous 1949 movie The Third Man – for ten long years, until 1955.

[Karlskirche by Fischer von Erlach]

* WORLD HERITAGE 101 *

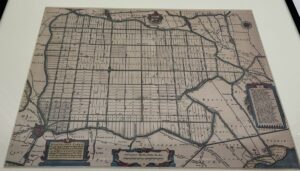

The Historic Centre of Vienna was classified by UNESCO in 2001, as it beautifully showcases the medieval and Baroque architecture and urban planning that characterizes central european cities. Vienna, for many years the capital of the long lasting Austro-Hungarian Empire, is also an important place when it comes to intangible heritage since it has been a major focal point for musical creation since the 16th century, being the city of famous composers like Mozart and Beethoven.

* JOURNAL *

DAY 10: The Ringstrasse

In the latter part of the 19th century, Vienna was in need to expand its dense urban medieval perimeter. The medieval walls of the city were demolished and a new, major boulevard – the Ringstrasse – was built, surrounding the historical town. This major project encompassed noble, representative public buildings and enabled the city to incorporate the developing suburbs, resulting in the quick enlargement of the capital.

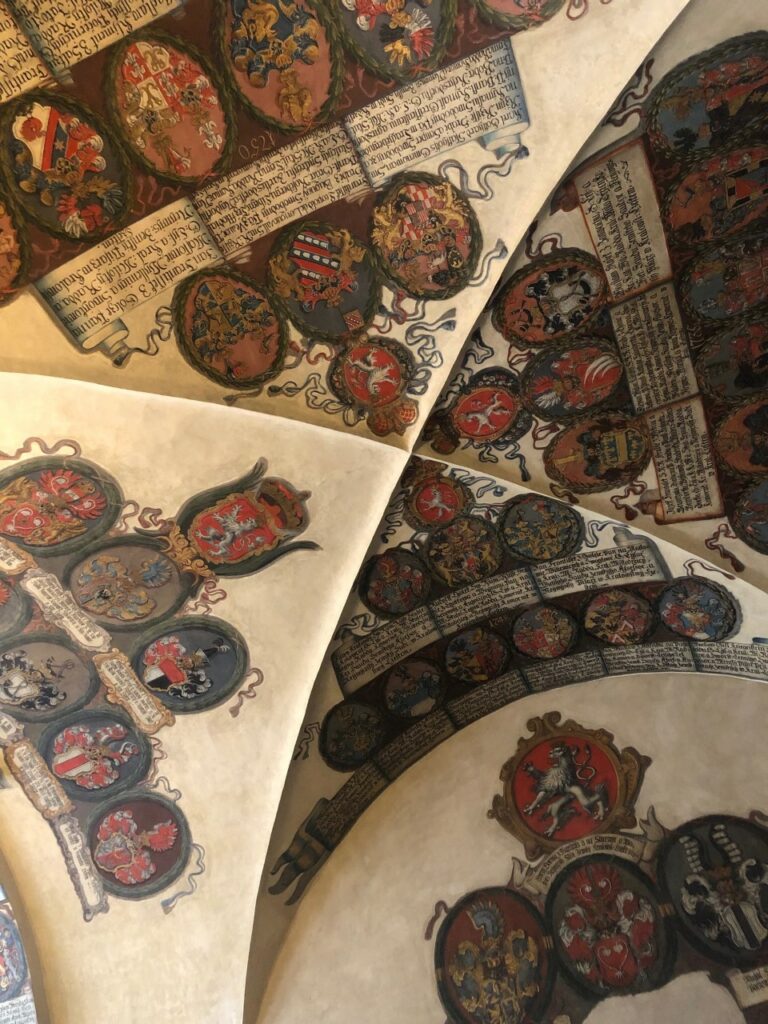

I spent my first day in the austrian capital walking along this main axis and got the opportunity to visit some of the magnificent buildings and parks that surround it. I started at Karlskirche, a major example of Baroque and of the spirit of the counter-reformation. This church is a major project by probably the most relevant Baroque austrian architect, Fischer von Erlach. From the top of its cupula, it is possible to admire the Vienna’s city center and how it stays course and coherent in a beautiful overlap between the different architectural styles that shape the city.

[The magnificient Baroque decor inside the church]

Then I continued my trip around the Ringstrasse to admire other buildings like the Wiener Staatsoper – the famous opera house, destroyed during WWII and reopened in 1955 with Beethoven’s “Fidelio” -, the Austrian Parliament – currently going through works in accordance to its original project – or the Wien Rathaus – the magnificent city hall building in neo-Gothic style.

DAY 11: Traces of Annexed Austria

My second day in Vienna was dedicated to visiting traces of the Anschluss, a very challenging period of occupation for the city and its inhabitants. My morning started at the Augarten, a public garden in the northern limit of the historical center that used to be a noble property and today is a extense public garden.

In the middle of the greenery, two massive structures disrupt the landscape: the Flak Towers. These enormous constructions were erected by the Nazis as anti-aircraft defense during WWII, resourcing to slave labour. Vienna was not the only city getting them: both Berlin and Hamburg were also equipped with a couple of them. Even though their immediate purpose was to block Allied offensives, there were plans to revamp and make them major symbols of Nazi power once the war ended.

[On my way to the Augarten / One of the Flak Towers]

Nowadays, it is interesting to reflect upon how each people and each city dealt and deals with this somehow “uncomfortable” heritage. The majority of these towers in Germany were either partially or totally destroyed right after the end of the war as they evoke the dark times of the war and the destruction it caused, while in Austria, most of them still stand, serving as a memorial and a public awareness tool for the harsh aftermath of conflicts in cities.

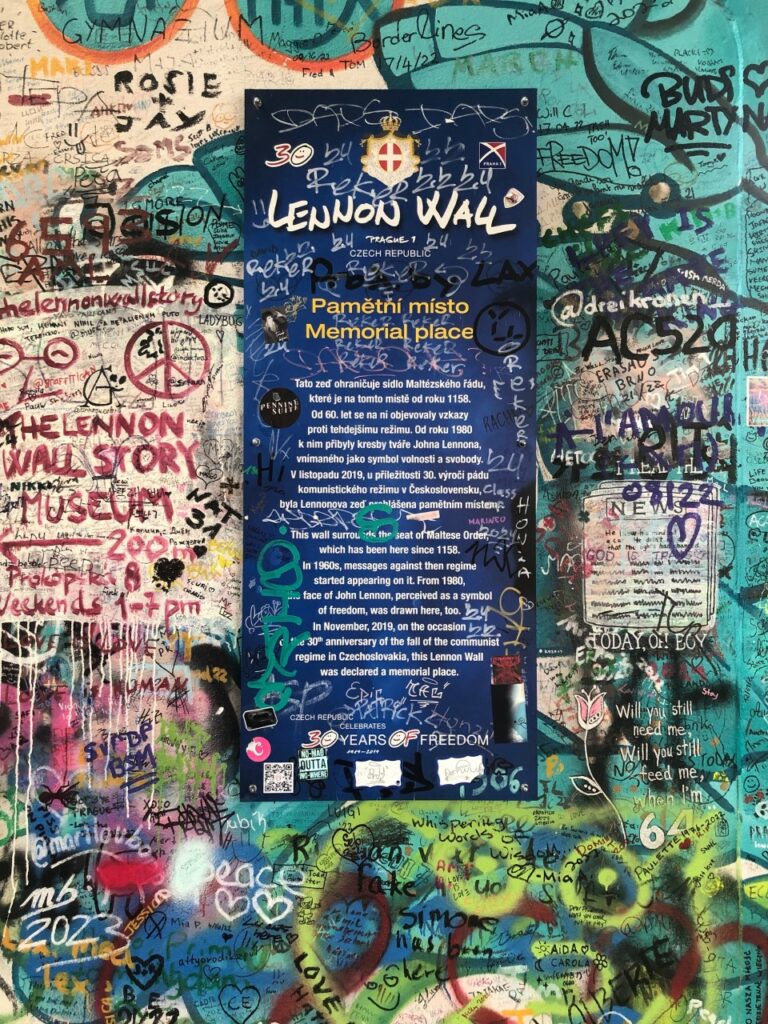

In the afternoon, I strolled around the city center and entered the Stephansdom – the city’s cathedral. From there, I walked through the thigh knit and classically harmonious settlement surrounding the royal Habsburg complex, passing by the Judenplatz – that used to be the center of the Viennese Jewish community in the Middle Ages – to check the site-specific that was built there – a petrified library, where books cover are not readable and where it is impossible to enter, remembering the cultural loss and the identity attack suffered by the jews during Nazi rule.

[A passage in the city centre / Judenplatz]

I ended my walk near the Albertina museum, where I made a last stop to appreciate one of the Hrdlicka Memorials. These small sculpted ensembles, created by the homonymous sculptor, evoke the many ways Austria witnessed suffering during the occupation and the war. The ones in the picture, in Albertinaplatz, use stone sourced using forced labour in Mauthausen, a concentration camp near Linz.

[The Royal complex / The Hdrlicka Memorial in Albertinaplatz]

DAY 12: A Divided City

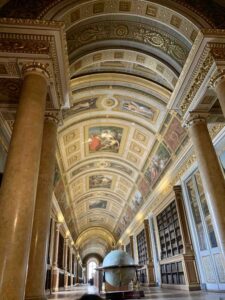

I could not finish my days in the Austrian capital without a visit to Schönbrunn Palace, the major summer residence of the Habsburgs. Together with its sumptuous gardens, the ensemble has been inscribed in the UNESCO list for World Heritage Sites since 1996. The building that can be seen nowadays has an original Baroque project, by same architect as the previously mentioned Karlskirche, Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach, but the full complex nowadays is the result of a sum up of many interventions throughout the centuries.

[The Schönbrunn Palace / The Baroque fountains / The Gloriette]

Curiously, after the war and during the Allied occupation period that followed (1945 – 1955), the palace was used for both the British Delegation to the Allied Commission for Austria and for the headquarters for the small British Military Garrison present in Vienna, before becoming a museum again with the reestablishment of the Austrian Republic.

Back to the city center after lunch, I visited a beautiful church – Dominkanerkirche – that illustrates Austrian Baroque well – white and intricate. Before leaving for my next stop, I still had time to meet Regina Wiala-Zimm, the International Relations Officer for the City of Vienna that cooperates directly with OWHC, and a fellow traveler, Stefan Župan.

* HERITAGE HIGHLIGHTS *

– Heldenplatz –

In front of the royal palace of the Habsburgs, the famous Hofburg, there is this significant square. In 1938, when the Nazis occupied Austria, Hitler did an impressive parade and speech here to show its power and announce the annexation of the country.

[Heldenplatz nowadays]

– Stephansdom –

The cathedral of Vienna, a magnificent gothic church, suffered tremendously during WWII. Damaged during bombing, as Germans were retreating from the city by the end of war, intentional destruction was planned. Viennese german command Sepp Dietrich ordered the soldiers to “fire a hundred shells (at the cathedral) and leave it in just debris and ashes.” Luckily, a subordinate disregarded the order and more destruction was spared. After the war, efforts to reconstruct it started immediately.

[The Stephansdom / The Canova inside]