To reach my last stop – Warsaw -, I took a bus trip that allowed me to sightsee the calm and harmonious Polish countryside. Starting as a smaller settlement, the city’s importance rose when, in the late 16th century, Sigismund III decided to move here, together with his royal court. Since then, Warsaw never lost its role as the capital city – of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, until 1795, and subsequently as the seat of Napoleon’s Duchy of Warsaw. In the 19th century, the city industrialized itself and by the beginning of last century, it was one of the largest and most densely-populated in Europe.

[The reconstructed Old Town of Warsaw]

* DURING WWII *

On the 1st of September of 1939, the first bombs were dropped on Warsaw, right after followed by a three-week-long siege. As the first big city to offer fierce resistance to Nazis, heavy losses happened: thousands were killed and about 12 per cent of all buildings were destroyed.

The five long years of occupation that followed brought even more despair and destruction. Nazis even drafted the Pabst Plan, a project that aimed to fully erase the city to build on top a “new german” one. That, fortunately, never happened, but intentional destruction happened on multiple occasions, to purposely attack Polish identity, culture and heritage.

Between 1942-1943, the Jewish Ghetto was built, the biggest ever established in the occupied countries. There, many perished and were deported to concentration and extermination camps. Destruction of the city and its people never ceased until the end of the war; right before it, the Warsaw Uprising, added an extra layer of rubble to the already fustigated city. By 1945, Warsaw was not much more than ash.

* WORLD HERITAGE 101 *

As a recognizement of the detailed reconstruction work that Warsaw witnessed starting right after the cease fire, that contributed to the verification of conservation doctrines and practices, the city became a World Heritage one in 1980.

* JOURNAL *

DAY 15: A Night Stroll

Upon my arrival, I was greeted by a local civil engineer, Piotr, who did an evening tour with me through the main axes of the city. He showed me interesting reconstruction projects that often do not make more mainstream suggestions, but that illustrate well the city’s reconstruction post WWII and the different facets it took.

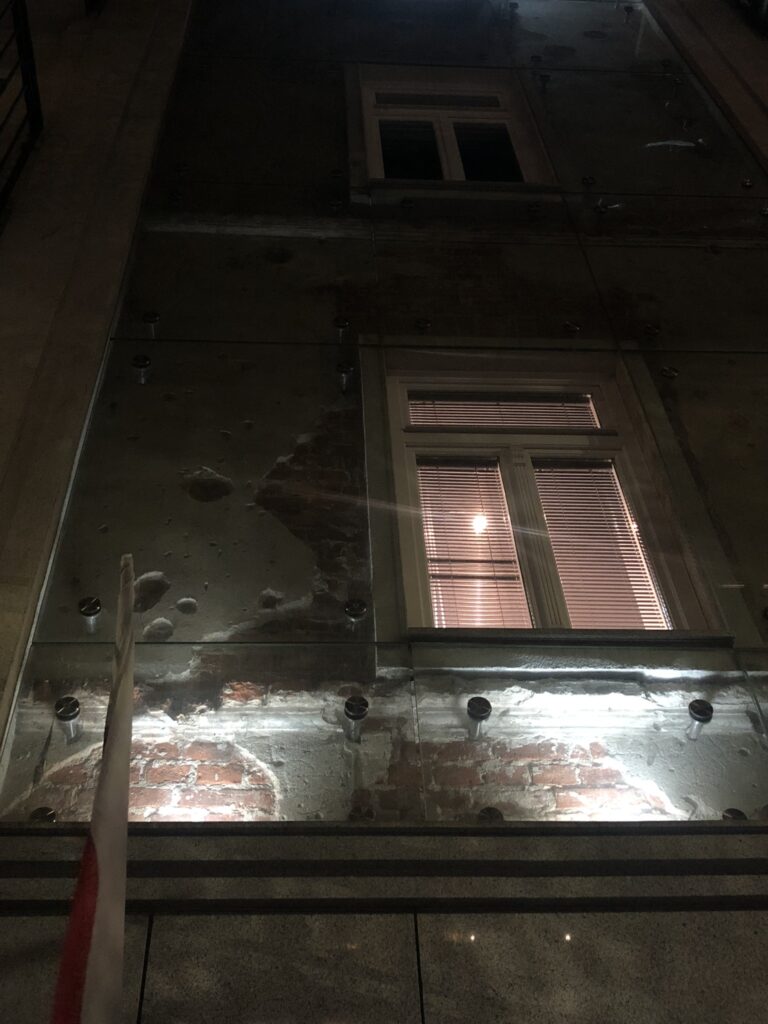

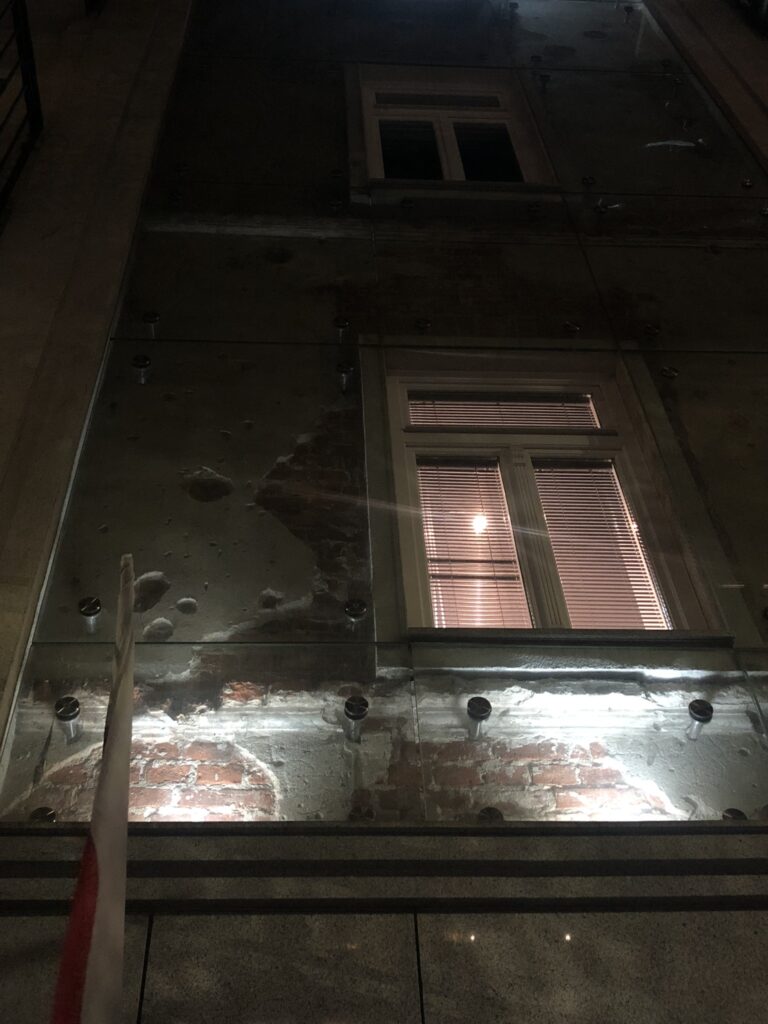

[The first skyscrapper is Wrsaw, with the symbol of Polish Resistance / A residential building whose recently rehabilitation chose to uncover the signs of war in the façade]

DAY 16: Warsaw, the Fenix

My first full day in Warsaw, started with a visit to the reconstructed Old Town. After WWII, 90% of the buildings in Warsaw were damaged. The new government led a plan to reconstruct the city center using an historical approach. By 1966, all of the monuments of the old city were re-erected according to their appearance between the 14th and 18th centuries. Today, there is a small interpretation center that tells the story of how all of that was done, that truly deserves a visit.

The Heritage Interpretation Centre is located in one of these buildings that was carefully reconstructed, in a small, picturesque street, right below the Old Market Square. There, I not only learnt more about the state of the city in the aftermath of the war, through photographs and videos made in the months that followed, but also how this rose many questions on how to rebuild such a large settlement almost from scratch.

[The photos of the reconstrution inside the exhibition]

Unwilling to gave up on Warsaw as the capital of the country, Polish people took the rapid reconstruction of the city as a task of national significance. The works started right after the liberation. Through the Decree of October 1945, the new communist government made all land within the administrative boundaries of Warsaw municipal property; a controversial measure that sped up the all process. Many architects, engineers, historians and sociologist were involved. The main guiding tools: Belloto’s veduti of the city, dating back to the 18th century, a debatable choice taken by the authorities, even though there was extensive footage kept from the pre-war and war periods. Some think this option better evoked the grandness of Warsaw in the eyes of those in power, as it coincided with a flourishing period of Enlightenment.

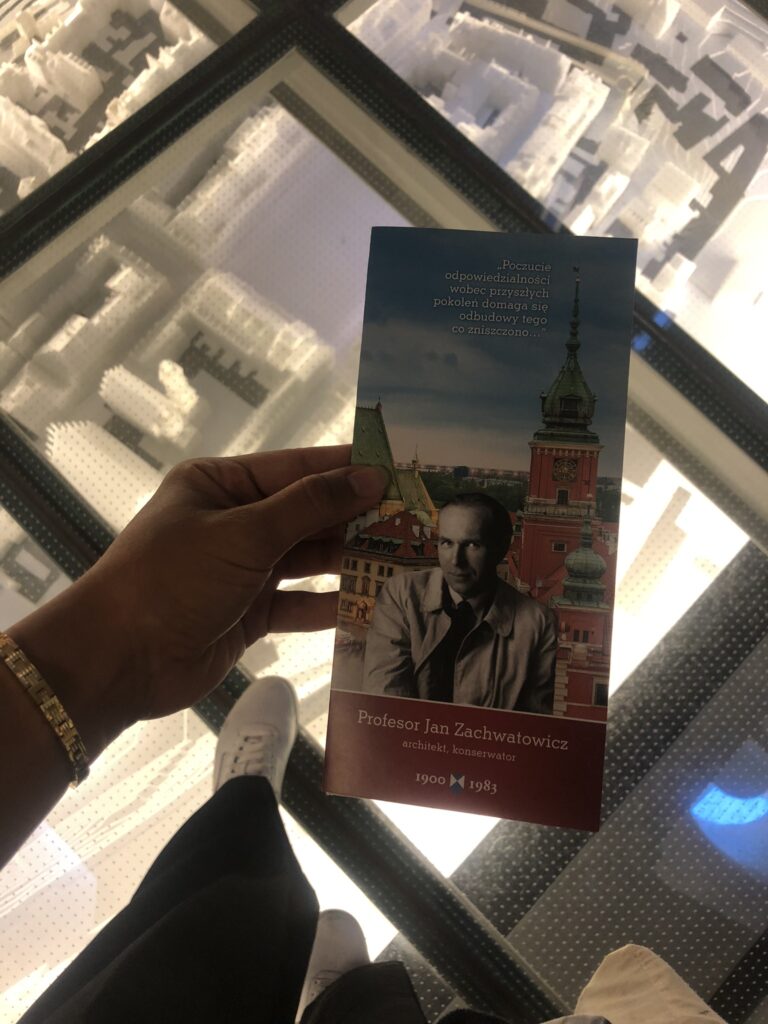

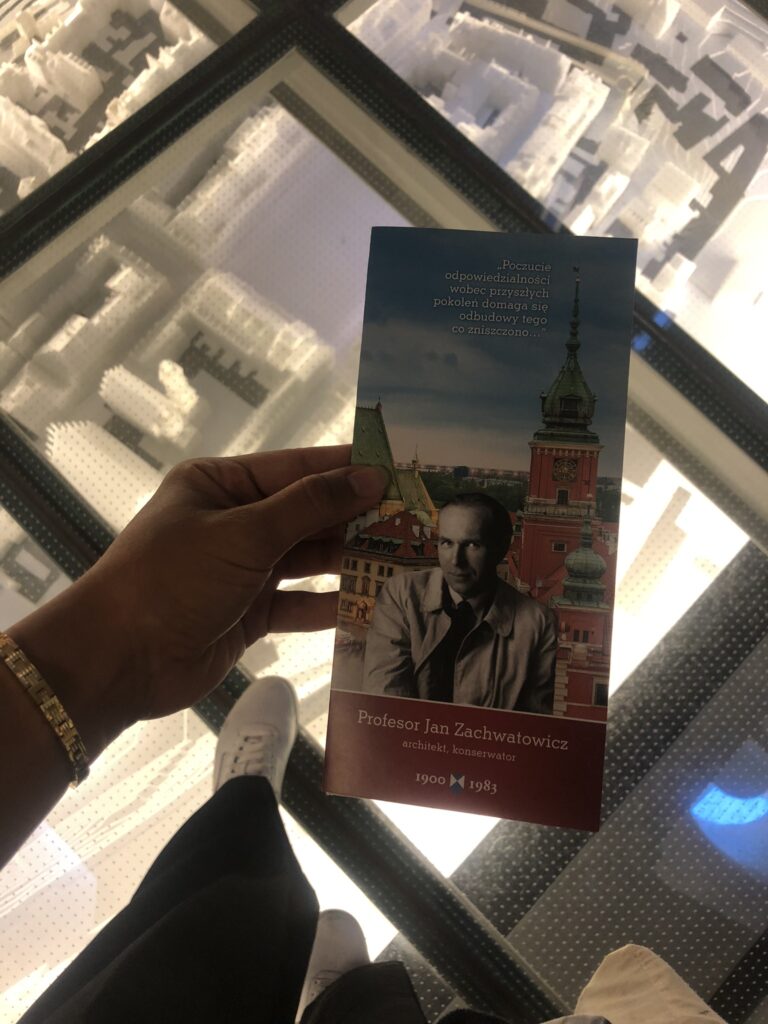

Through the exhibition, I also got to learn about Jan Zachwatowicz, who from 1946 onwards was in charge of the Warsaw Reconstruction Office and its Department of Architectural Heritage. Zachwatowicz undertook massive efforts to ensure an authentic reconstruction of the Old Town, refusing both a modernistic project or leaving the city like it was to serve as a memorial of all the destruction inflicted. From preserving original mansory that had survived structurally intact for later reconstruction to leading a surprisingly short completion of works – 4 years for the heart of the city only -, the architect left a tremendous contribution to its profession. Zachwatowicz was also the author of the Blue Shield – a symbol of protection that identifies cultural property to be protected in the event of armed conflict, ruled under the Hague Convention of 1954, the first international treaty to state the importance of safeguarding heritage under war, as a result of the catastrophic effects of WWII. During the rest of my stay in Warsaw, I saw copious amounts of this sign throughout the city.

[Jan Zachwatowicz / One protected building by the Blue Shield]

In the afternoon, I did a free walking tour around Muranóv, a neighborhood which used to be a part of the city ghetto. We started on the border of the Old Town and the old Warsaw Ghetto, around Krasinski Garden, which portrayed how Varsovian Jews had a story of persecution much older than the dark chapter of the 20th century. In a time when they were expelled from Warsaw, rich noblemen rented plots and wooden houses to the Jewish population in the back of their properties, already outside of the city. Krasinski is one of those cases. When the Warsaw Ghetto was established by the Nazis in late 1940, one of the main doors stood nearby and today it is still possible to see the patches covering bullets markets in the wall surrounding the garden.

[The wall of Krasinki still holds signs of the war / The previous place that used to be occupied by the Ghetto Wall / One of the memorials to the Ghetto resistants]

Muranóv itself was completely erased by the Nazis with explosives after the Warsaw Ghetto eradication in 1943, it was impossible to rebuilt it like the Old Town. Nowadays, even the road structure is different from what it used to be. The memory of the lost neighborhood and its heritage is celebrated here and there with small memorials but remains almost unnoticeable for those that are not informed on the topic.

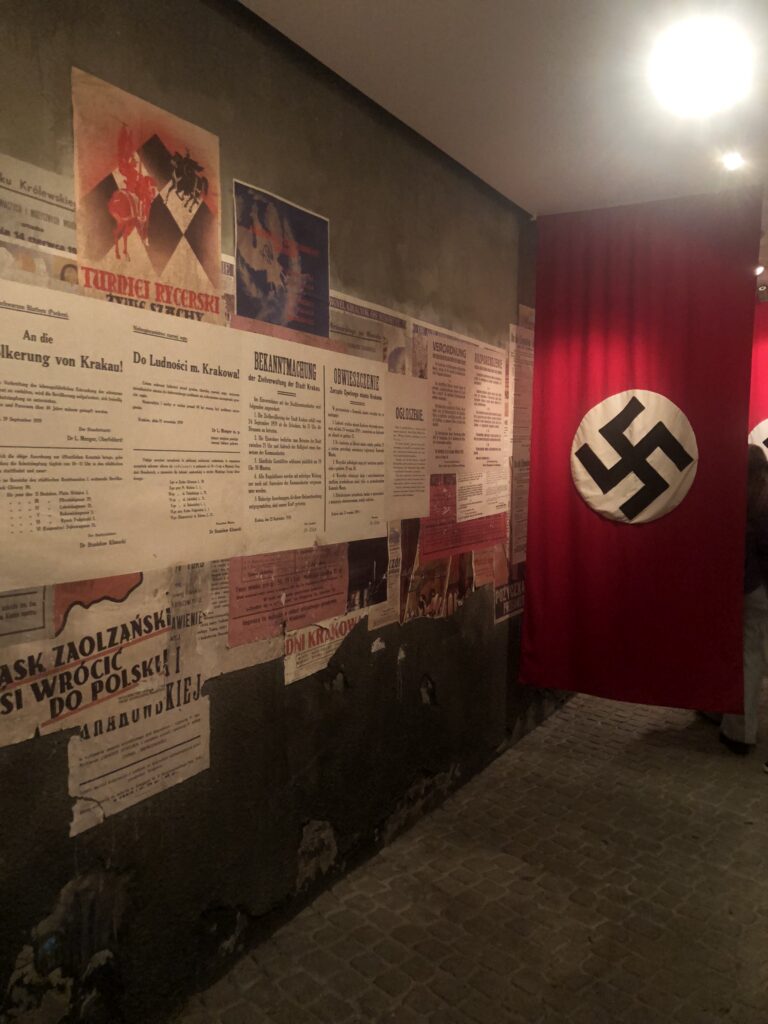

DAY 17: The Jewish Ghetto

On my second day in Warsaw, I visited the Warsaw Rising Museum, to better understand how the Polish people fought for their independence, culture and city during the times of occupation. There had been a first uprising in 1943, right before its eradication by the Nazis, which was unsuccessful. On the 1st of August 1944, the remaining city was exhausted and willing to fight back one last time. Its underground resistance launched an operation to try to liberate Warsaw from Nazi Germany. Supposed to last only one day, it took more than a month, ending up with the resistance’s defeat. The city, that had already been extensively bombed, saw even more inhabitants perish and became even more damaged damaged during these days of street confrontations. Just like the first, the Warsaw Rising failed its purpose but the exhibition tells its story day by day and highlights brave Varsovians that took part on it, including brave photographers and videographers that lost their lives in an attempt to document the damage made to the physical structure of the city.

[Original remains of the bombed Royal Castle / A replica of the sewage system of the city that was used to communicate and escape during the war]

In the afternoon, it was time to check some buildings that, impressively after so many decades, still await reconstruction in the city, some landmarks that were rebuilt after severe reconstruction and the few remains of the ghetto wall.

I passed by the St. John Cathedral, in the heart of Warsaw, which is a marvelous example of post-war reconstruction of heritage. Originally built in the 14th century, in Masovian Gothic style, it was almost erased during the Warsaw Rising in 1944, when the German army intentionally destroyed it – by placing explosives on the foundations of major landmarks. After the end of the war, it was rebuilt to look like it’s presumed original appearance, using 17th century illustrations and drawings. A similar approach was used at St. Anne Church, at the start of the Royal Route, which I also had the pleasure to visit.

[St. John’s Cathedral on the background]

My late afternoon was spent hunting for the few remains of the Warsaw Ghetto walls still remain, partly because Germans, after the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, tried to eradicate all the evidence of their crimes, partly because they are a painful memory that was not always taken into consideration during the reconstruction of this area of the city in the 50’s and 60’s.

[The Church of the Visitadines, rebuilt according a Belloto’s veduti / One of the few remains of the Ghetto Wall]

DAY 18: From Bellotto’s Veduti to a Reconstructed Capital

Last day in Warsaw and last day of the trip! I couldn’t leave the city without paying a visit to one of its more notable and grandiose reconstructions, the Royal Castle, originally built in the early 17th century, when the Masovian dukes moved the capital from Kraków to Warsaw. There, the first national constitution in Europe was signed in 1791. In 1939, the castle was targeted by Luftwaffe – the German Air Force – and, in 1944, detonated by the Nazis after the Warsaw Uprising. Reconstruction only happened between 1971-1974, financed by the Polish people, since the communist government that ruled Poland after the war showed resistance when it came to rebuild a building that was associated with monarchy.

[The magestic Royal Castle, with its Belloto’s collection]

After I passed through what remains from the Saxon Palace, one of the most impressive buildings in the Royal Way before WWII,also heavily destroyed during the war. The small fragment that remains now hosts a memorial. There are plans to reconstruct it soon, in a costly and majestic historical approach. As of now, it is a major example of the planned destruction Nazis performed in Warsaw – destroying heritage to weaken the enemy and their culture, memory and identity.

To finish my stay, I went up to see the city from above, making a last stop at the Palace of Culture and Science, a post-war building, a gift from Russia to the city in the 50’s. Looking in one direction, one can see the picturesque old town rebuilt, in the other the area where the ghetto used to be, where now there are big skyscrapers together with typical communist housing blocks built in the 50’s, 60’s and 70’s: a striking contrast.

[The Palace of Science and Culture / The view from above]

Nevertheless, Warsaw filled me with a lot of hope regarding what is now sadly happening once more, in the neighbouring Ukraine. Seeing what can be done when people unite to safeguard their common history, re-ignited my trust that after the 20th century and all its tragedies, some lessons were learnt and we are now, colectively, in a position to take cultural heritage protection as a serious affair, with true social and economical implications, and not just like a good-to-have that can be forgotten during times of conflict!

[With Piotr, local civil engineer, and my my long-time friend Marharyta, an ukranian architect, at a milk bar, tasting some Polish traditional food]