With a hasty and comfortable train returning to Berlin, I enjoyed the remainder of my Wednesday afternoon with leisure. My hostel was located in the southernmost area of the city (the catch for booking the cheapest hostel room), but luckily it was placed adjacent to Osdorfer Straße Station, giving me efficient metro access to and from the city within 30 minutes. I enjoyed myself in Berlin, but it was quite the adjustment coming from Brussels. My first impression was of course noting the expansive suburbs in which I found my temporary stay. The impression was calm, organized, and uncanny-American. I realized quickly (having known the feeling my whole life) that I was back in a very cartesian realm, one in which a foot-peddlar like me would have some diffculty. Fortunately aside from the area’s lack of laundrymats, absence of grocery stores, and slow late-night transit during the weekdays, my first impression of Berlin was somewhat false. In the city center I found much of what I needed with reliable transportation and at medicore (but acceptable) distance to one-another.

Bottom line, Berlin is a big city. It felt to me very idealistically American with its car-centric city-planning, its industrial consumerism (liquidation stores, fast food, etc.), and its respect to the suburban life. In a way, it seemed like the common lifestyle that the U.S. tries to achieve, with the added bonus of reliable suburban transit and affordable (or even free) public recreation. Conversely, the construction of Berlin’s suburbs feels much more authentic: houses are detailed with better hardware and more durable finishes. They also each have a quirky, stylistic touch of German vernacular; not the copy-paste, thirty-year-lifespan shacks that have gained popularity with contractors in the U.S.

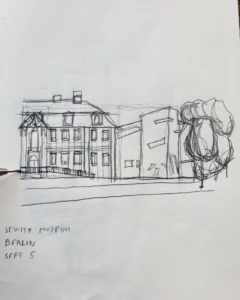

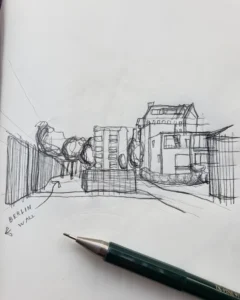

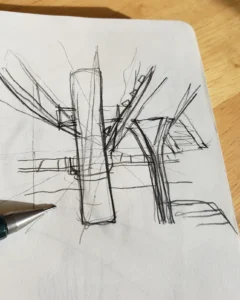

During my frequent trips to the city center, I absolutely had to visit one of my favorite pieces of architecture for the first time: David Libeskind’s Jewish Museum. One of the first buildings I thoroughly studied in university, this museum was constructed using countless techniques to give the occupants feelings of hopelessness and false-optimism as a memorial to the Holocaust. I took my time with this one, rejecting the audio-tour to experience the building and its content in the intended silence. In the same day I traveled to the Berlin wall. An earlier recommendation was to explore the pocket-neighborhoods along this memorial, so I attempted to view as many as possible. Of course as I imagined, it was quite a long distance to walk, but each new block offered a unique urban environment and used the wall in a slightly different manner. I was happy to see such a complex memorial footprint being so naturally integrated into the modern city.

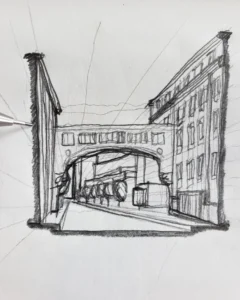

Night life in Berlin was the liveliest I had ever witnessed. The most cosmopolitan scene I found during my stay was in the bar and club districts, and it lasted for the entirety of an owl’s waking day. These clubs were found in something I’ll call a Ber-limbo, a ring layer between the city center and the suburban outskirt that held the industrial, manufacturing, and otherwise unnattractive city-zoning: the perfect hub for night-life.

Although my hostel was empty aside for one new companion, I was able to quickly make friends who were traveling as well. With them I learned that night-life in Berlin is quite exclusive and can cater to quite a specific clientele; regardless, I enjoyed myself, and it was refreshing to be surrounded by so many lively, fun-having, young-adults.

If I were to return to Berlin, I would certainly prefer to bring a friend. For someone who is moderately social, I think it would be wise to travel in familiar company in such a vast urban setting. Vast is no exaggeration, as I still find myself getting lost in a simple map of the city. However in the time I alotted myself, I believe I gained a reasonable familiarity with Berlin, one from which I can employ similar city-planning techniques in my career’s far future.